The Board for Certification of Genealogists has codified the industry’s standards for proof into the Genealogical Proof Standard. This standard has five components:

- Thorough (“reasonably exhaustive”) searches in sources that might help answer a research question.

- Information (“complete, accurate”) citations to the sources of every information item contributing to the research question’s answer.

- Analysis and comparison (“correlation”) of the relevant sources and information to assess their usefulness as evidence of the research question’s answer.

- Resolution of any conflicts between evidence and the proposed answer to a research question.

- A written statement, list, or narrative supporting the answer.

These parts are interdependent and their combination is what leads to solid research and analysis that is less likely to be overturned except by the discovery of a record to which you had no access at the time of your written statement.

| Research Question: | Narrow enough to have limited answersBroad enough to be answered with records of a place and timeShould not contain assumptions |

| Citations: | Citations in our written work serve multiple purposes: Remind us where we got the information Tell others what sources we used Indicate the reliability of our sources Citations use standard formats with standard components: Who – the source’s author, creator, or informantWhat – name of the sourceWhen – date of publicationWhere in – box, volume, or page number within the sourceWhere is – location of the source (it is probably not available at every public library) If a second part of the citation is needed to describe the medium, separate them with a semi-colon and answer the same five questions. |

| Analysis and Comparison: | Why was the source created?What was the time elapsed between the events and the report?Was the author or record keeper professional and careful?Was the source open to challenge and correction? (court testimony)Were they protected against bias, fraud, and tampering?Did experts evaluate the authored source?Did the writer of an authored source use the least error-prone sources?Does the source show signs of alteration at any point in its history?Does the informant show potential for bias?Was the informant reliable as both observer and reporter? Related sources duplicate each other [death certificate, obituary, tombstone]. Independent sources corroborate each other [birth certificate, draft card, obituary]. |

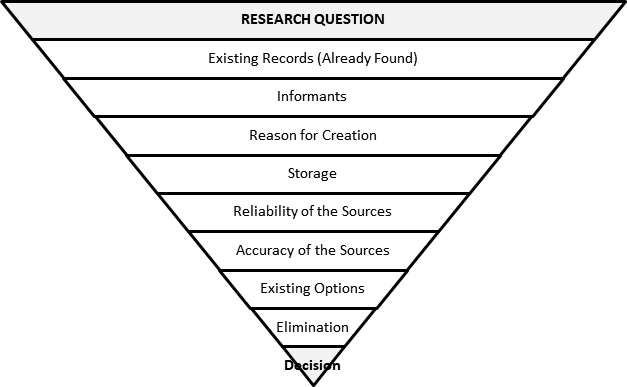

| Conflict Resolution: | Separate the evidence into likely correct and likely incorrect Discard the incorrect answers Justify / Explain the separation and discarding Effective Explanation: Identifies two or more answers in conflictLists or describes evidence supporting each sideDemonstrates resolution due to:Lack of corroborationQuality of evidenceLogical explanation Do NOT force a resolution – sometimes the evidence is just not yet available |

| Evidence | Suggests answers to research questions Categories: Direct – answers a research question all by itselfIndirect – a set of items that suggest an answer when they are combinedNegative – the absence of information that answers a research question |

| Sources | Authored works – present a researcher’s conclusions, interpretations, or thoughtsRecords – note, describe, or document an action, event, observation or utteranceOriginal – made at the time of the event or soon after – not based on prior recordsDerivative – created from prior records – transcribed, abstracted, translated, reproduced The type of source helps you to evaluate: potential for errorneed to pursue original recordsthe credibility of a conclusion |

| Information | Surface Content Physical Appearance Categories: Primary – reported by an eyewitnessSecondary – reported by someone based on receipt from someone elseIndeterminable – source is unknown Informant – someone who provided information of interest |

| Source Narrative Example | Direct evidence of the marriage between Vena Anderson and Gustav Bergquist on 5 September 1923 in Buxton, Maine is found in a full photocopy of their original marriage certificate. Handwritten, and showing different writing styles, the certificate was most likely completed immediately after the ceremony at the direction of Rev. Alexander Stewart and is signed, in their own hands, by Claus Bergquist and Florence Emery as witnesses.1 |

| Written Narrative: | Watch for proof statements and proof arguments as you read previously published materials on your family. Consider the following aspects of what you are reading in order to reach your own conclusion on the veracity of the author’s work: Is a clear research question stated?Do the citations:encompass sources likely to help answer the question?reflect a search that was reasonably thorough?demonstrate that the sources were reliable?Does the writer justify the use of any error-prone sources or information?Do the footnotes and text include the writer’s analysis of the sources?Is the conclusion based on the correlation of evidence for all relevant sources?Is the conclusion presented with correlations in text, list, table, map and other applicable formats?Are all conflicts resolved with evidence supporting the conclusion?Is the conclusion clearly stated?Does the author show why their conclusion is correct? |

Conflict Resolution Narrative:

References:

- www.BCGcertification.org : Board for Certification of Genealogists, P.O. Box 14291, Washington, D.C. 20044.

- The Board for Certification of Genealogists. The BCG Genealogical Standards Manual. Orem, UT: Ancestry Publishing, 2000.

- The Board for Certification of Genealogists. Genealogy Standards (50th Anniversary Edition ed.). New York, NY: Ancestry Publishing, 2014.

- Evidence: A Special Issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly, volume 87, number 3 (September 1999).

- Jones, T. W. Mastering Genealogical Proof. Arlington, VA, USA: National Genealogical Society, 2013.

- Merriman, Brenda Dougall. Genealogical Standards of Evidence: A Guide for Family Historians. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Ontario Genealogical Society, 2010.

- Mills, Elizabeth Shown. Evidence Analysis: A Research Process Map. Washington, DC: Board for Certification of Genealogists, 2007.

- Evidence!: Citation & Analysis for the Family Historian. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1997.

- Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2007.

- Rose, Christine. Genealogical Proof Standard: Building a Solid Case. 3rd. rev. ed. San Jose, CA: CR Publications, 2009.